Title: «Solaris«

Author: Stanislaw Lem

Pages: 571

Edition: Unknown (version translated from the French by Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox)

Publisher: Unknown.

Genre: Science fiction

Year: 1970

Language: English

Format: EPUB

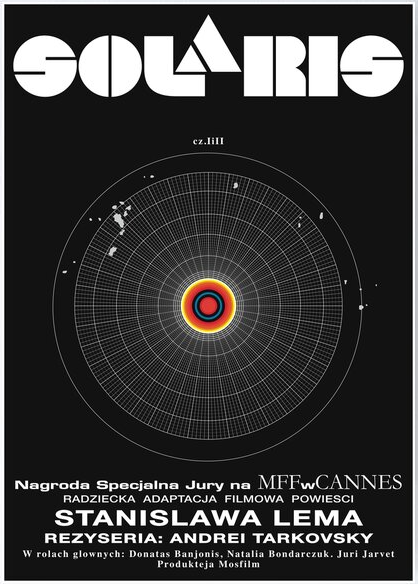

I asked ChatGPT about the greatest book on science fiction, and «Solaris» was its recommendation. I checked the Kobo Store for an electronic version of the recommended book, but I didn’t find anything, so I searched online. Yes, I found one in PDF format that I converted to EPUB. The file didn’t come with a cover, so I searched for one and found what I think is a poster for Andrei Tarkovsky’s film (which I believe Lem severely criticised). It was added during the conversion process, so I can upload a «whole book» into my Kobo reader.

In broad strokes, the story recounts a phenomenon occurring on a planet with a single, enormous ocean. This planet orbits a binary star system: a red giant and a blue dwarf. The stellar interaction causes gravitational perturbations on Solaris, whose ultimate stability can only be explained by the balance the ocean provides through its mass redistribution.

I found the beginning of the story boring and slow. It wasn’t until I reached the section describing Solaris’s ecosystem and all the research conducted in the decades leading up to the protagonist’s arrival on the planet that the story became interesting, and I understood why this LLM had recommended it to me.

Although there are three human characters in the story, I believe that, after the main character, the next most important is the ocean of Solaris, as it is presumed to be a sentient or conscious entity, given the care dedicated to the planet’s orbit. Lem’s detailed description of the ecosystem this being represents and its manifestations reminded me of Fred Hoyle’s «The Black Cloud,» as well as Frank Herbert’s account of Arrakis for his «Dune«.

ChatGPT mentioned in its recommendation that the work involved a particular philosophical debate, but didn’t provide any details. As one progresses through the story, the human drama unfolds, stemming from the way the ocean of Solaris interacts with humans. This interaction occurs in an unexpected way, where the last thing one would imagine is that the sea seeks to establish communication. It simply happens that the human presence provokes something in the ocean, leading to the materialisation of what the ocean of Solaris manages to «see» of the human psyche.

Thus, throughout the book, this reasoning leads the protagonist to understand that the ocean may not even be aware of human presence. For the ocean and its material manifestations, the human presence is like a speck of dust. Unlike Hoyte’s work, this book presents an entity that, while conscious, possesses a consciousness incompatible with or incomprehensible through human reasoning—perhaps superior, perhaps inferior, but entirely different and thus difficult to assess in terms of capacity.

From my perspective, I even think that it might not be conscious at all (according to human understanding). One could argue that the vast ocean of Solaris is nothing more than a biological machine, set in motion aeons ago, which has achieved a highly complex and almost conscious equilibrium, yet without truly being so.

In conclusion, this is an entertaining but not light read; I would even say profound in its connotations. It’s not the kind of space opera many readers expect.